South of the capital city, Ørestad is a developing urban quarter growing out of a metro line placed between Copenhagen's historical downtown district and the city's international airport, located on the island of Amager. Burdened with low economic growth and high unemployment at the end of the 1980s, the Danish Parliament passed the 'Act of Ørestad' in 1992 (first Act of Parliament in thirty years where the state was involvement in a major new urban development project), creating the idea for a new major urban development scheme that would act as a 'city annex' attracting innovative national and international ventures, supported by a series of important infrastructure investments including a new metro line and the Øresund Link (tunnel/bridge project to Malmö, Sweden). Financing such an expansive project would be inspired by the English New Town principles, to which new infrastructure be subsidized by the incremental land value created by the very same Metro. By building Ørestad, Copenhagen not only financed the Metro, but also a new urban quarter that would usher Copenhagen out of financial crisis and create a testing ground to display the city's new ideas in architecture and city planning. In 1994, the winning project of an international architectural competition by a Finnish-Danish architecture studio (KHR Arkitekter) revealed an overall masterplan for Ørestad, dividing the area into four smaller districts, focused on integrating a highly-dense and modern city with the surrounding natural environment, forming attractive recreational access and sustainable planning to future residents / companies of the area.

“It is the intention to give full artistic freedom concerning architectural form, so that the new city quarter of Ørestad will boast state-of- the-art within architecture and art during the building years.”

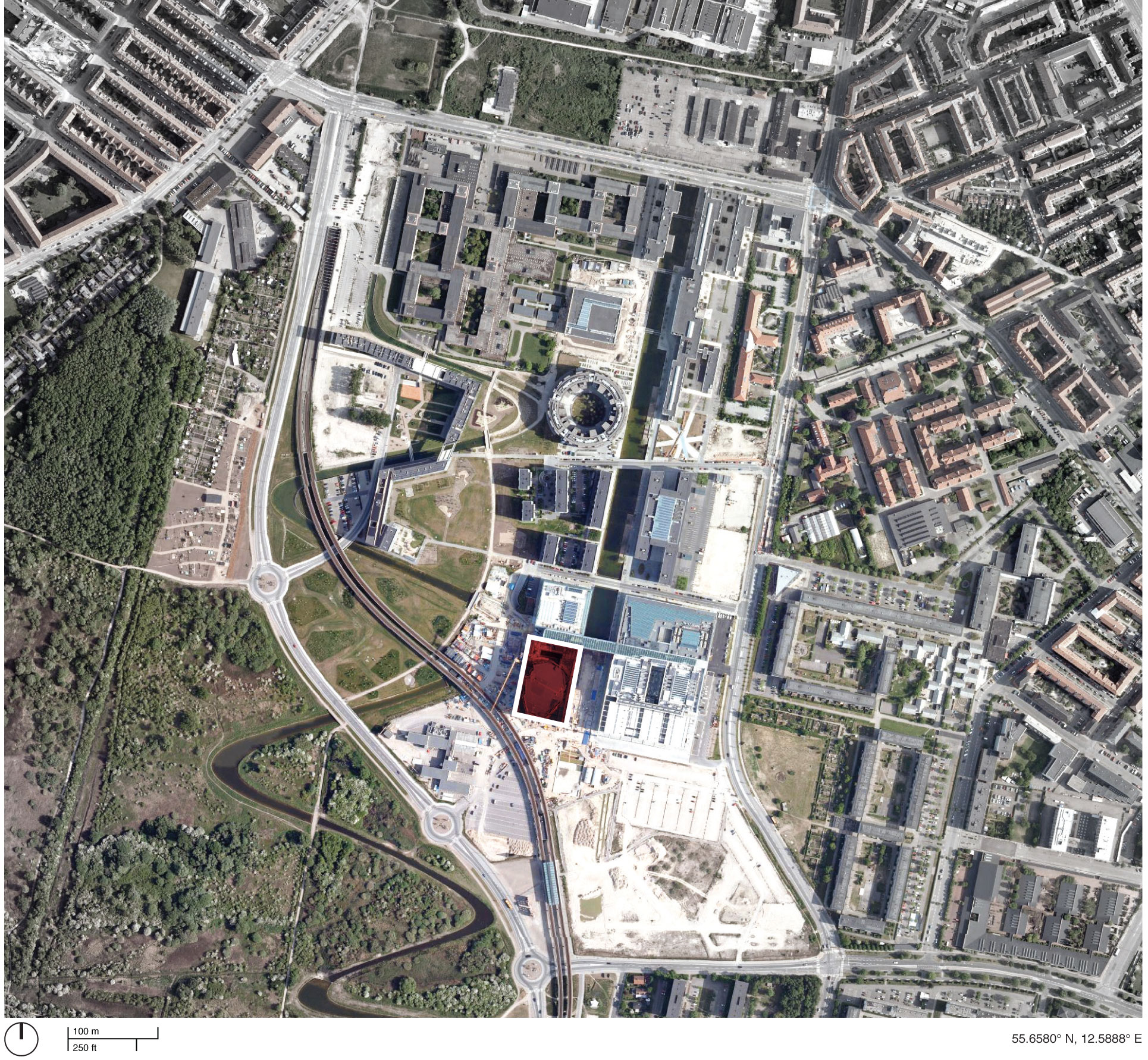

Area of Ørestad's urban quarter between Copenhagen's historic downtown area and the international airport. Red area locates Ørestad North or 'University District'.

KHR Arkitekter's masterplan for the University of Copenhagen and Ørestad North, 1997

Located off the first new Metro stop from Copenhagen, Ørestad North (University District) is the most developed of the four areas of Ørestad. Focused around the masterplan's idea of a central "village green", the Landscape Canal and the north-south-oriented University Canal define the new urban construction of The University of Copenhagen-southern campus. Each building would ensure contact to a functional outdoor space and the strong axis of the artificial University Canal, creating a powerful pedestrian hierarchy with a connection to nature. In 1999, state-owned Danish media company (DR) decided to join Ørestad North's campus to concentrate all of the company's activities from the metropolitan area into one address. DR Byen (DR's new headquarters, referred to as 'DR City') is a four-component complex that would account for all Danish Radio’s offices, TV, radio, and orchestra productions under one roof, even including a new state-of-the-art concert hall (Koncerthuset) for the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, further advancing Ørestad's goal of promoting progressive arts and technologies in the region. Unfortunately, DR Byen's construction process accumulated a range of controversial public outcries over budgetary concerns, allegedly due to the complexity of the concert hall, leading to high-profile resignations and drastic cutbacks in DR staff and public funding. In all, the entire project would cost almost three times as much as budgeted (up to $300 million), making the DR Concert Hall one of the most expensive concert halls ever built.

Back in 2002, Jean Nouvel would win the competition to design the 590,000-square-foot concert hall, as the fourth and final segment to the DR Byen project. As the yet-to-be-finished 'gate to Ørestad', the site would prove to be problematic as it was clustered on a barren site in an emerging neighborhood, wedged between the new elevated metro and the remaining unfinished DR Byen projects. The architect would react with caution to the untested local conditions, as it was not reliable to judge the newly built-up surroundings with an urban potential that is impossible to evaluate. With no urban response, the question had to be switched. How can this project contribute to and survive the future of this site? According to Nouvel, the response would be the mystery of uncertainty. "The proposal consists of materializing the territory and providing it with the scale of an exceptional urban facility. It will be a volume that will allow its interior to be guessed."

Sitting behind the dematerialized envelope of blue glass-fiber skin that is draped over a commanding steel structural frame, the theater becomes an architectural anomaly. One that seeks to hide behind a curtain, but still calls for attention. Nouvel’s design approach, both the container and the auditoriums and spaces within assume a vastly different character depending on the time of day you visit. During the day, the project sits as the figurehead of North Ørestad's artificial canal, caging a shadowy figure that cannot be accessed with public intrusion, only to open at night as an ethereal object with the glitz of lights and images on the screened envelope, becoming a beacon of light 148 ft up in the air, calling to oncoming visitors. It is an urban alarm clock that can't be set, only to awake the surrounding context when it wishes. The only problem is the site has not fully awoken to the theater's tantalizing images, a stark opposition to the sterile desolation around it with swaths of undeveloped land with tufts of grass and mounds of dirt extending around it.

“Building in emerging neighborhoods is a risk that has often proved fatal in recent years. When there is no built environment upon which to found our work, when we cannot evaluate a neighborhood’s future potential, we have to turn the question around: what qualities can we bring to this future? We can respond positively to an uncertainty by using its most positive attribute, that is, mystery. Mystery is never far from seduction.”

Model displaying the interior workings of theater

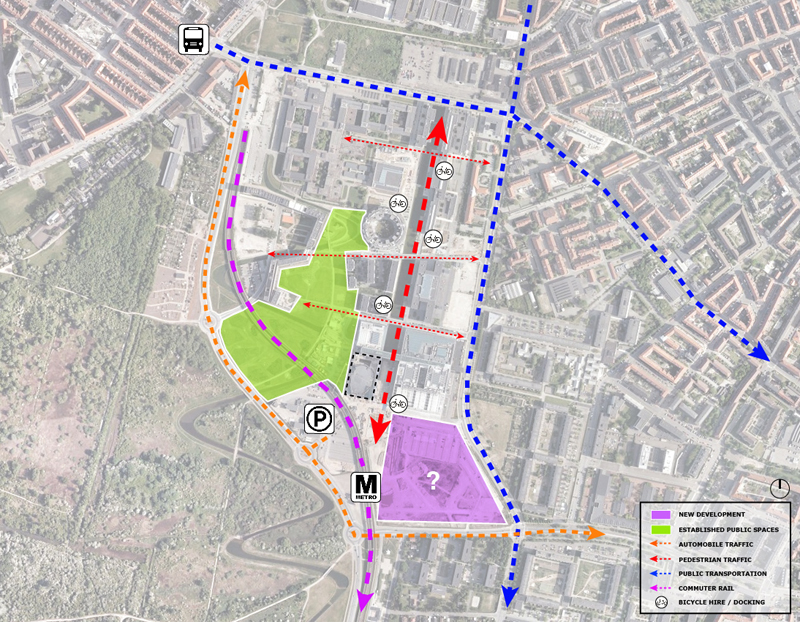

DR Concert Hall / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement