The pursuit for a prominent musical complex to showcase Rome’s famed National Academy of St Cecilia (Accademia Nationale di Santa Cecilia) has been an ambitious undertaking - one that has lasted over 65 years of competitions, postponements and uncertainty. In 1936, the historic auditorium (the Augusteo) - and home to the 425+ year-old institution’s Symphony Orchestra - would be dismantled to recover the ruins of the Emperor Augustus Mausoleum buried beneath. In the years that followed, the National Academy of St Cecilia was forced to rent existing structures throughout the city center as it pressed the municipal administration for available urban space to construct a new concert venue. A 1950 design competition considered the expansive and available Flaminio district of Rome as a new home for the Academy, only to result in an indeterminate recommendation from the jury - putting the project in a state of uncertainty for years, though highlighting Flaminio as an ideal and practical location for future development.

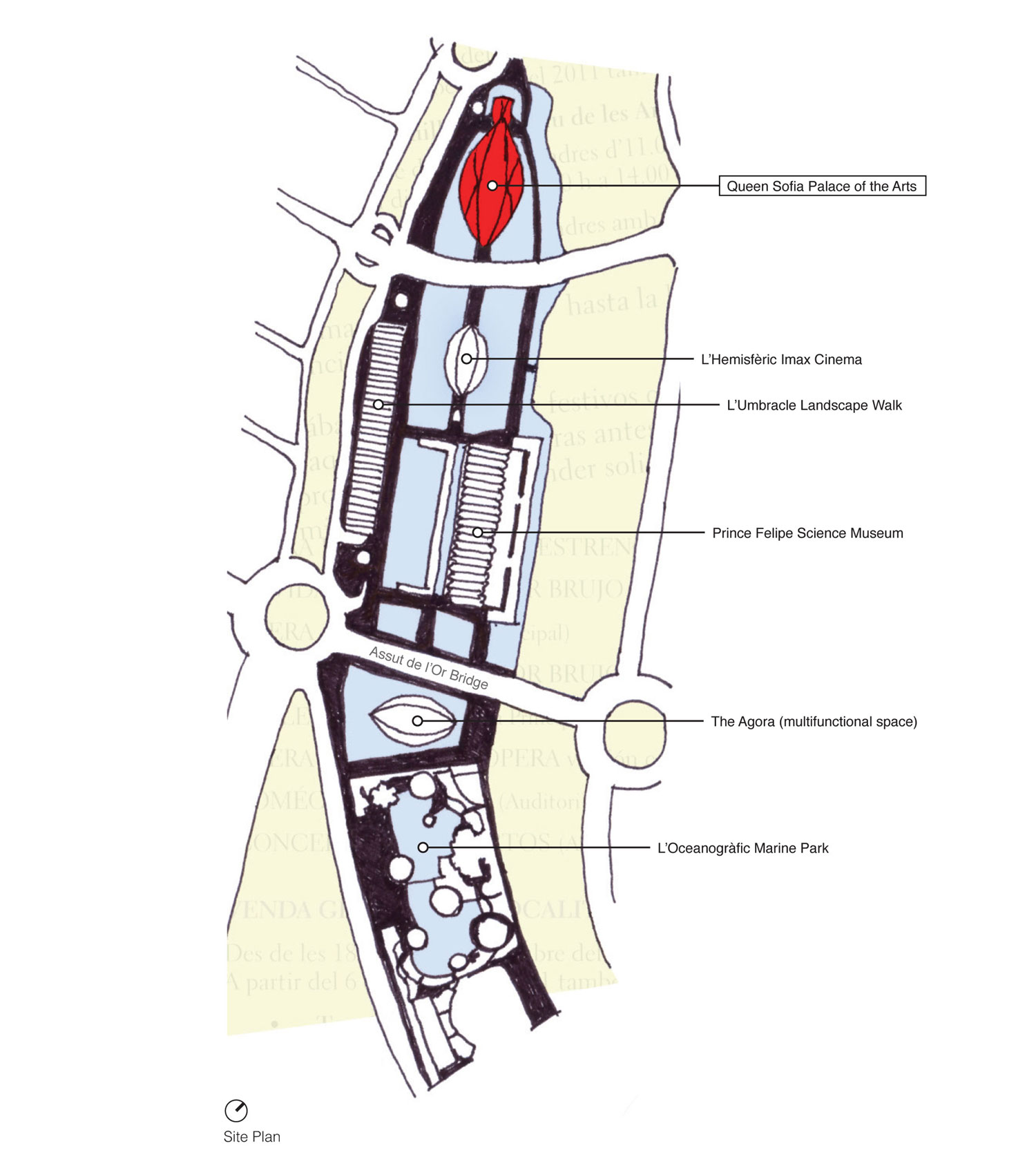

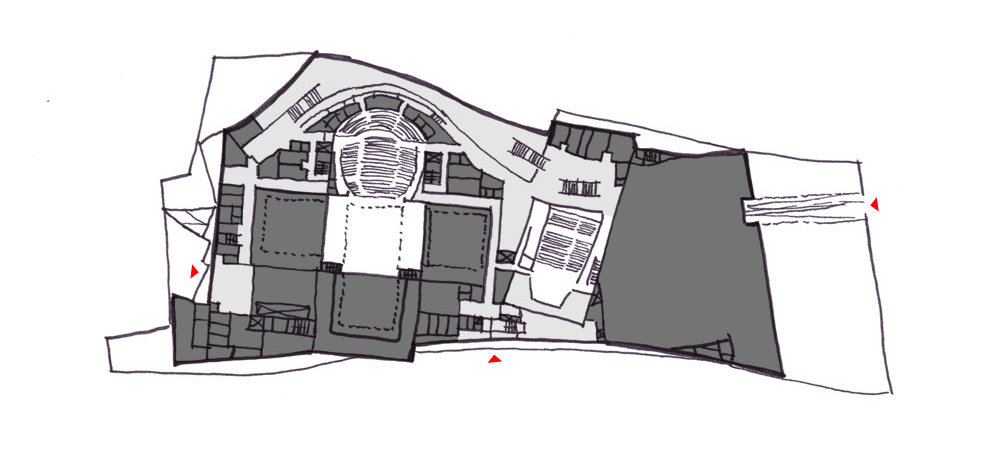

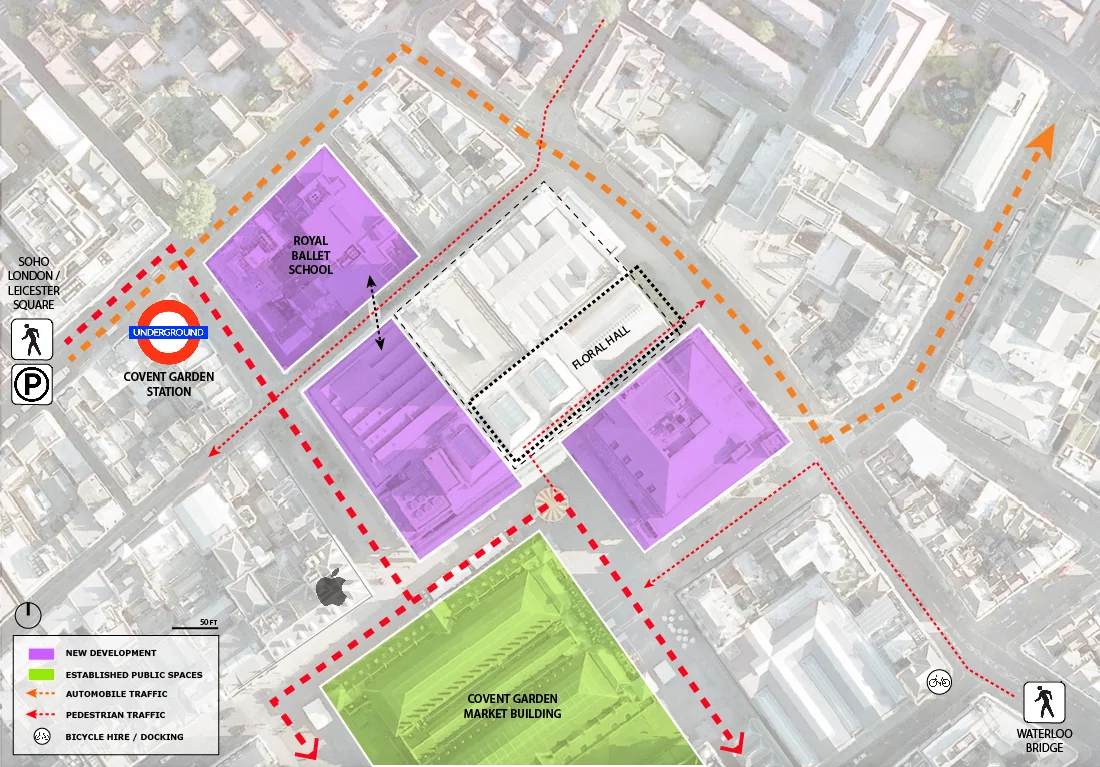

Site Diagram : Auditorium Parco Della Musica

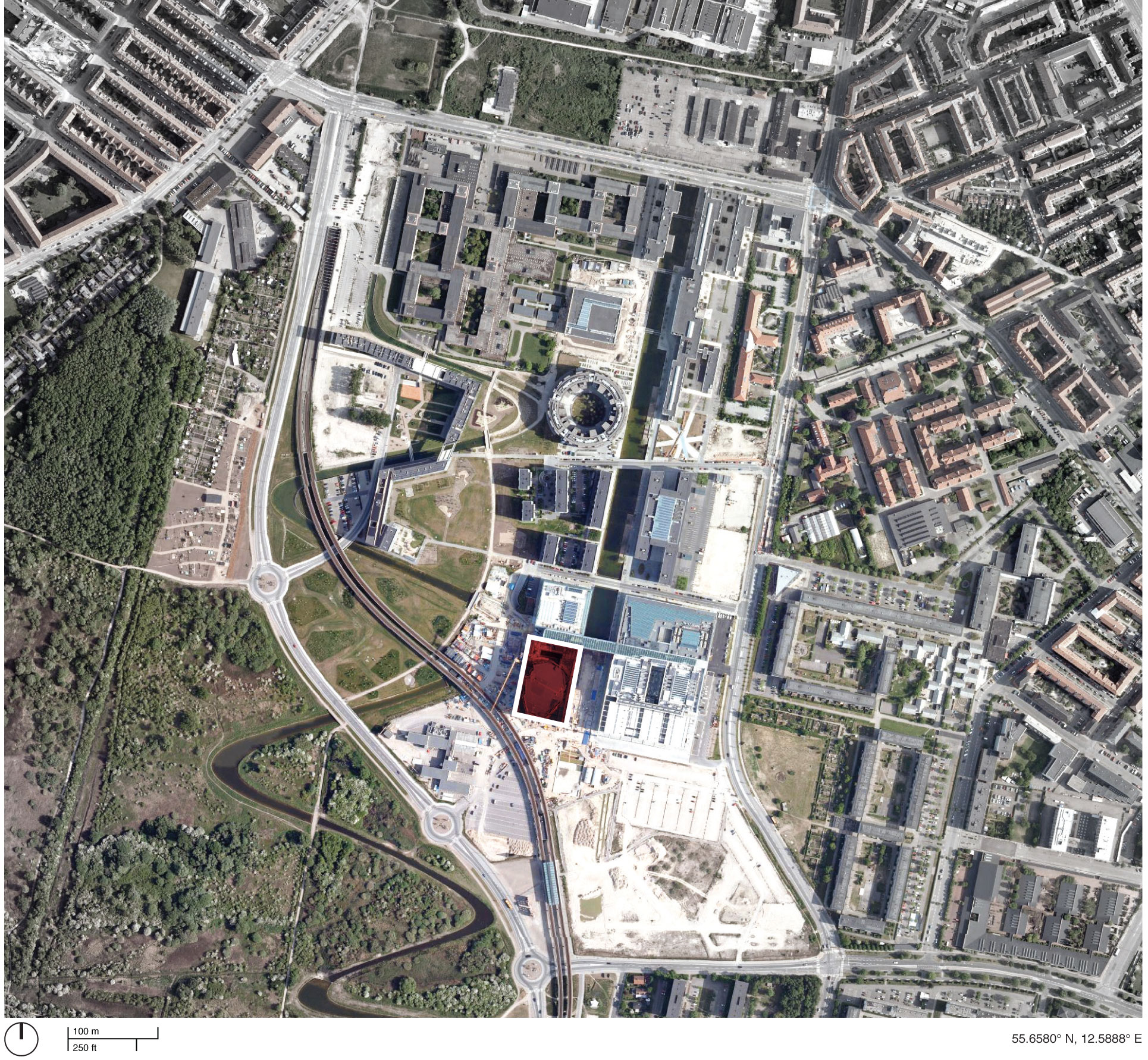

Flaminio District's current context

The Flaminio district, located north of the city’s historical center in the curve of the Tiber River, is named after the ancient road of Via Flaminia that leads from Rome over the Apennine Mountains to the Adriatic Sea - a major trade route in the Roman Empire. Excluding the Flaminia road, the flood-prone area outside the Aurelian walls was largely untouched until the end of the 19th century when industrial enterprises overran the region. With the industrial implant established, a period of settlement expansion would occur with an increase of building complexes and road networks. In 1911, city officials selected the Flaminio district to host Rome’s International Exhibition of Art in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Unification of Italy - initially defining the area’s ubiquitous character as a cultural, entertainment and sporting locality for the city. Following the announcement of the Rome Olympic Games for 1960, Flaminio would enter a new phase of urban transformation as the selected site for the new games - with construction of the Olympic village, Olympic Stadium, and the Sports Palace (along with the previously-built Flaminio Stadium) a catalyst for change in post-war Rome that is still omnipresent today.

Covered entry arcade with access to the site’s public commercial activities (shops & restaurant)

Seating for the open-air amphitheater

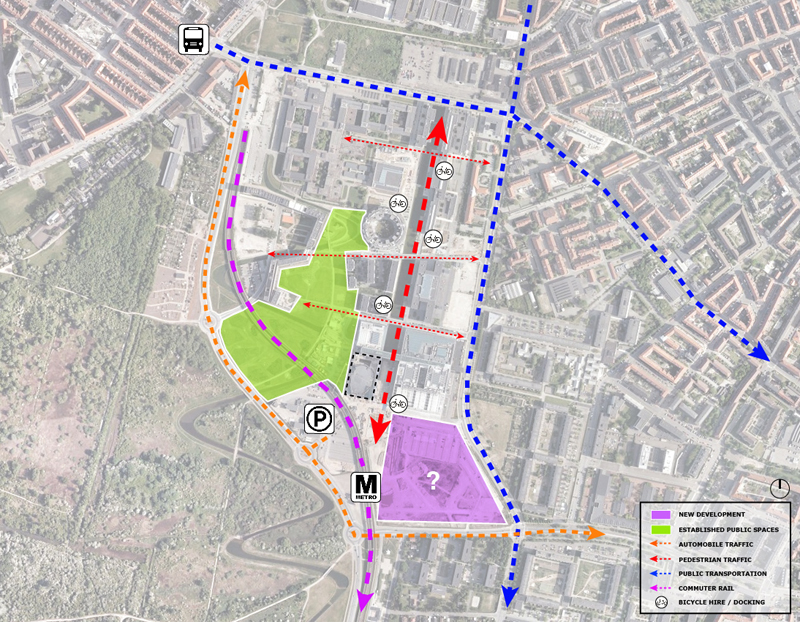

In the ongoing effort to alleviate Rome’s lack of adequate venues for classical music, the Rome City Council decided to host an invited international design competition in 1993 for a new music complex. However, such a desired large complex would not be feasible in the very dense historical center of Rome near the Accademia’s prior venues. Therefore, the competition site would be positioned in northern Rome, on a spacious former parking lot site in the Flaminio district - bundled between the former Olympic structures. The Olympic Village extends northward of the site, Pier Luigi Nervi’s ‘Sports Palace’ (Palazzetto della Sport) to the west, and the Flaminio soccer stadium to the south-west. The following year, Italian architect Renzo Piano and the Renzo Piano Workshop were named the winners of the competition with a scheme that offered a modern concept of landscape urbanism to weave the scattered fragments of the Flaminio district. With the completion of the new Auditorium project, Rome’s Flaminio district would again go through another chapter in urban development - one that requalifies the region as a contemporary neighborhood focused on the arts and sports - further emphasized by the recent completions of the MAXXI (Museum of XXI Century Arts) by Zaha Hadid in 2010 and the Ponte della Musica (Bridge of Music) by Kit Powell-Williams and Buro Happold in 2011.

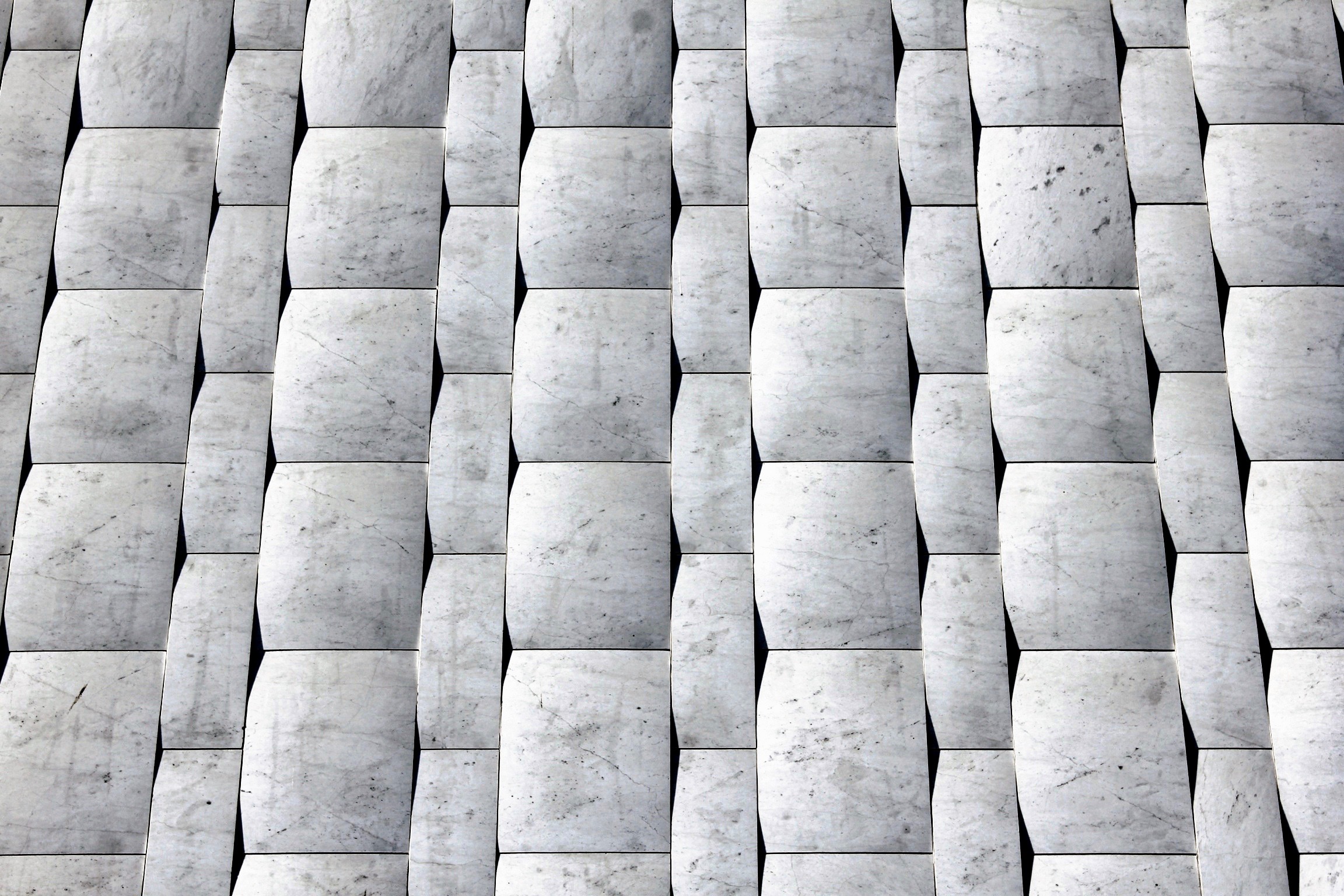

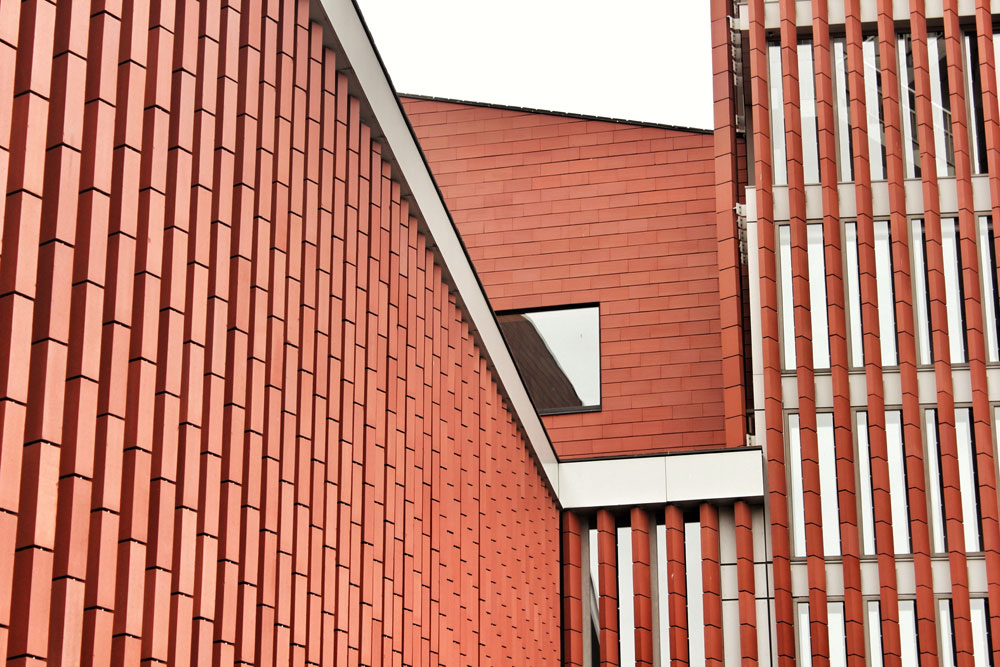

Zinc-shrouded roofs (a material resembling the historic lead domes of Rome)

Sculpted cultural elements composed around outdoor amphitheater and landscape

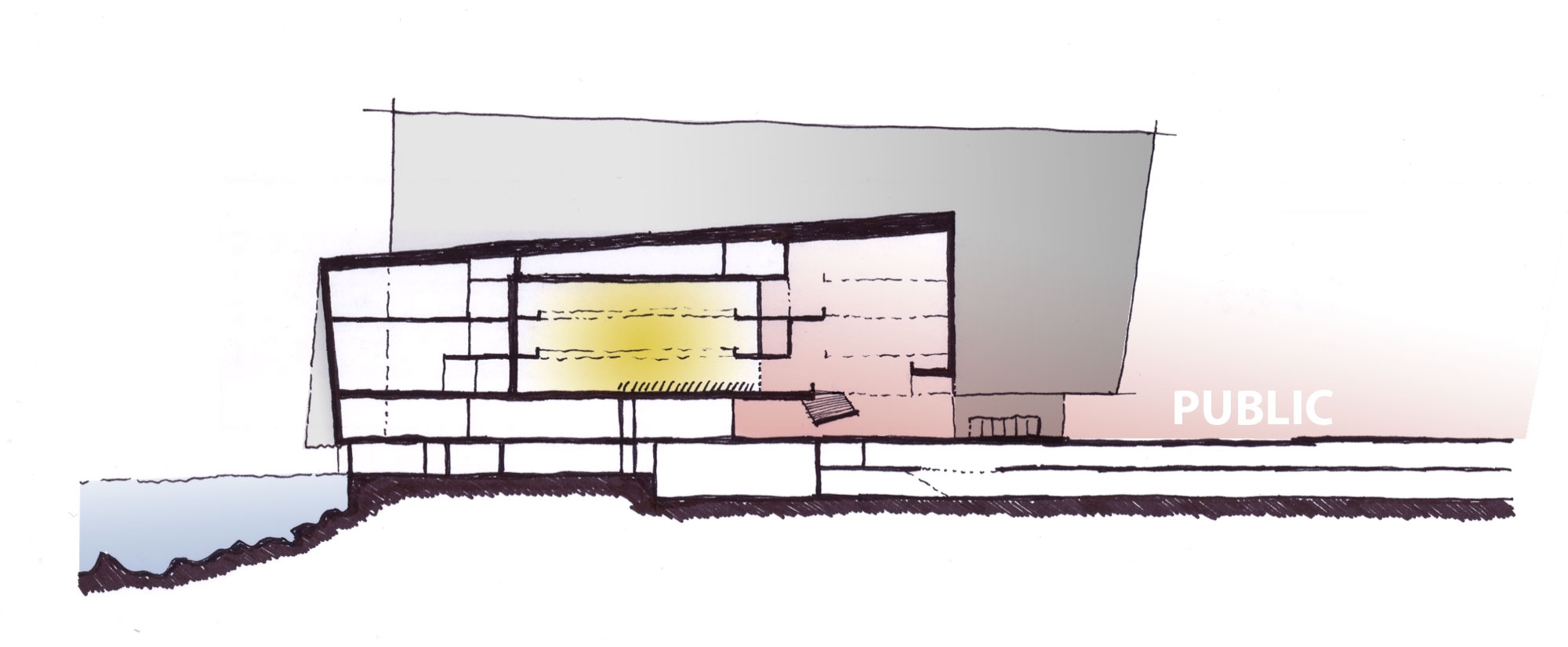

Auditorium Parco Della Musica / Site Section

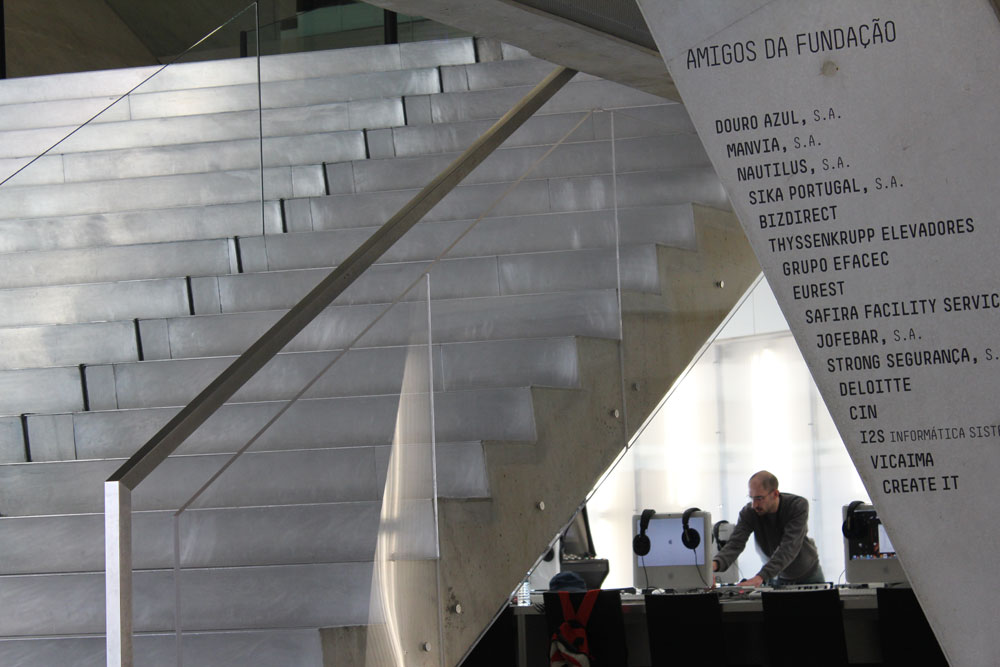

The project, later named the Auditorium Parco della Musica (Park of Music), is conceived as an open multi-functional complex to host a variety of musical performances on a decentralized site that benefits from a transportation infrastructure inherited from the 1960 Olympic Games. Not simply a performance hall, but a complete urban condition for music: with three concert halls, large rehearsal and recording rooms, workrooms, a museum of musical instruments, a comprehensive music library, retail shops, gardens, exhibition spaces, offices, bars and restaurants - all radiating around an active open-air amphitheater or ‘Cavea’. Acknowledging activity adds an additional layer to the project - allowing urban participation therefore gives an urban sense of the complex - enriched by cultural nodes (concert halls) that are separated and submerged in the Parco della Musicas landscape, which rolls down from the neighboring Villa Glori. Each one of the three concert halls is understood as an individualistic element, architecturally and functionally separated to facilitate soundproofing and coinciding performances, but aesthetically tied by identical zinc-shrouded roofs (a material resembling the historic lead domes of Rome). It is the placement of these sculpted cultural elements - arranged by size and elevated around the amphitheaters concave stepped seating - that unifies the project’s composition, while the subterranean foyer below directly links the perimeter of the outdoor amphitheater to the Auditorium. The main entrance of the complex from Viale de Coubertin projects a glass-covered arcade with access to the site’s popular public commercial activities (restaurant and shops), while the more intimate park area - complete with playgrounds and grass fields - radiates beyond the halls as a quiet buffer between the complex and the city beyond.

Seating overlooking The ‘Cavea’ open-air theater, named ‘Largo Luciano Berio’

Auditorium Parco Della Musica / Hybrid Site Plan

Risonanze Area

When the project began excavation in 1995, work was immediately halted with the discovery of ancient ruins from a large farmhouse villa dating from an archaic era (6th century BC - 3rd century AD) - not an uncommon occurrence in Rome - consisting of different residential rooms around a central courtyard. The discovery of the archaeological remains delayed construction for a year and triggered a modification in the design with an adjustment to the building layout for integration of a museum for the Roman remains found on the site - proving the project’s fluidity and adaptability early in the construction process.

Ruins preserved within the Parco della Musica complex.

Ancient Roman villa unearthed during construction

Inaugurated in December 2002, the Auditorium Parco della Musica has been considered a healing element in Flaminio’s pocketed urban tissue and Rome’s arts scene. The multi-dimensional complex accommodates the diverse programmatic needs of the city - designed for symphonic concerts, ballets, contemporary music, opera, baroque music, and theater - with potential to significantly expand its range of activities to include different art and performances in support of the Music for Rome Foundation (a joint partnership between the City of Rome, Chamber of Commerce, the province of Rome and the Lazio Region). Recent urban growth, cultural production and historical connotation come together with this new complex to alleviate the urban fracture that was once a neglected parking lot. The whole area can now be considered a new park open to the meandering public - a synthetic and functional continuation of a landscape that stretches between the banks of the River Tiber and the nearby Villa Glori - redefining the Flaminio district as an integral part in Rome’s contemporary aspirations.

“ When cities expand there are always black, untidy holes that then need to be filled in. This is the real gamble of the next thirty years: how to transform the edges of the city of those areas over-looked by urban development. One of the ways of upgrading this emptiness is to create places that bring people together or fill them with collective functions.” - Renzo Piano, architect

Auditorium Parco Della Musica / Site analysis of access, circulation, new development, and points of social engagement